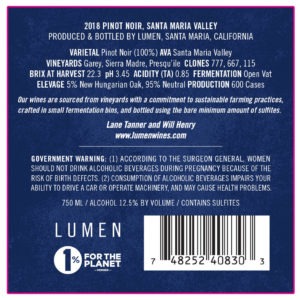

There’s a lot of geeky stuff on the back of a Lumen bottle – wine-geeky stuff. So why is it there? Not only are the basic facts listed – vineyard source, AVA, variety, clone – but also we share the pH, TA (titratable acidity), and Brix at harvest.

What, you may ask, is the significance of all that techie mumbo-jumbo?

All three of these data points help a winemaker see what kind of balance the fruit has, and ultimately, what balance the finished wine will be. This can mean the difference between a wine that tastes flabby (too little acid), to one that tastes too jammy (overripe, often which comes with flabby), or one that tastes too bitter or green (sugar too low and/or acidity too high).

pH and TA are both measurements of acidity. Think back to chemistry class and you will remember pH – it is a general measurement of acid vs. base balance in an aqueous liquid. pH of 7 is balanced – neither acidic nor basic. Grape juice (and hence wine) is generally in the 3 range – 3.2 being more acidic than 3.8. Generally speaking, the earlier you pick in the growing season, the lower the pH (and higher the acidity). TA is yet another way to measure acidity, and it can sometimes paint a more complete picture than just the pH alone. The TA basically gives a measure of the quantity of total acids in solution, while pH is simply a measure of their strength.

The brix at harvest is perhaps the most important measurement of all. Brix tells us the sugar content of the grapes in percentage of solution. Hence, 23 degrees brix means 23% sugar. Winemakers and winegrowers talk all the time about brix.

“So what is your vineyard at right now?”

“We seem to be stuck at 21 brix, but maybe after the heat wave this weekend it will shoot up a point or two.”

Then after two consecutive hot days, “Brix went up two degrees over the weekend. We are trying to get a crew in to pick pronto. But everyone wants to pick at the same time!”

This last conversation details one of the great challenges of making great wine. Nailing the pick day. As sugars increase in the grapes, acid decreases. A good winemaker will watch that balance closely as the grapes ripen, and then pounce when they see that moment of perfect balance. For Lumen, that happens when the brix is between 21 and 24, pH from 3.4 to 3.8, and TA of .5 to .8 grams per 100ml. But those are broad ranges, and the way that they interact tells a much more interesting story. For example, a wine that was picked at 3.4 pH and 22 brix with a TA of .8 would have, in my book, almost perfect numbers. It would be a wine worthy of aging, and should also be pretty damn good in its youth. A wine picked at 24 brix with .5 TA and 3.8 pH, however, is most likely going to be better in its youth, and not as age-worthy.

Some years are better than others, too. In the absence of large weather-related issues (i.e. heat waves, hail storms during growing season), vintage variation is largely due to subtle day-to day differences over the entire season. Cool years generally produce grapes with a higher acidity relative to sugar – which is why we like them so much. They may not be the best for number of beach days, but we will take the fog for better Pinot. My favorite kind of year (and this is not the same for all winemakers, mind you) is when I can pick my grapes at 22-23 brix and the acidity is still very high. That doesn’t always happen, though.

The other factor that greatly influences when we decide to pick is taste. Every single sample of juice, after it goes through chemical analysis, is then tasted by Lane and myself. That, more than anything else, is the deciding factor in choosing a pick day. The juice could be measuring 22 brix and 3.5 pH (which would indicate maturity), but the juice still doesn’t taste right. Maybe it’s still green and vegetal tasting, or maybe the fruit flavors just haven’t developed enough. In that case, we would have to make a tough choice to either let it ripen a little further, or pick before the acidity droops even further. It’s a touchy game.

Lane and I like to find the balance in grapes before making a wine from it. Well-balanced fruit means that we don’t have to mess with the wine at all – just ferment it, put it in barrel, filter it, add a teensy amount of sulfites and bottle it. Good fruit leads to wine with less additives, and more often than not, wine that will age longer and more gracefully.

Finding the balance, aging longer and more gracefully – isn’t that what we all want to find – not only in wine – but in life?